|

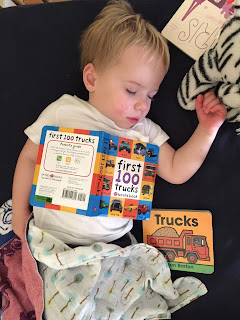

| Can't get enough! |

Will was born 3.5 weeks before my due date, so we were not at all prepared. I think a better phrase to describe us at the time would be in denial. I thought, "oh, I'm having a new kind of Braxton Hicks, but these hurt." I managed to keep that up until 5am, when it was clear we had to go to the hospital. We barely had a car seat -- it was still in its Amazon box -- so we did an overall pretty haphazard job of packing. We also lived an hour from the hospital, so there as no way to go back for the things we forgot. And one of the things we forgot was a book.

I was so crushed by this oversight that my husband ran out to the drug store and bought a book. It was not a good book. But Will had a bedtime story on the day he was born:

|

| Will with his Grandma Janet and Aunt Julia on the day he was born, April 21, 2014 |

This was important to me for the same reasons it's important to you; we've all heard it a million times; reading to children is the most important thing we can do for them. Reading, every day, from birth. Most parents know and agree with this position, even if they don't know exactly why.

As a literacy researcher, I also agree with this position, for two main reasons: reading to children builds literacy knowledge and literacy motivation.

First, reading aloud to children builds all the early literacy skills I've described in earlier posts. It builds language knowledge, most importantly, vocabulary. Reading aloud just as important to building language as talking to your child. Reading aloud is critical because literary language is very different from oral language.

In oral language, we tend to use casual, informal words over and over: "Hi, how are you? How as your day? What did you do at school? What do you want for dinner?" Vocabulary researchers conceptualize three "tiers" of words that children can learn (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2013):

Tier 1 includes all these common, every day words: happy, sunny, cold, diaper, bedtime. Children need these words to express their feelings and communicate with others, so they are very important! But by age 2 or 3, they understand and can use many or even most of these words. Conversations with your children are still very important, but the bulk of new vocabulary learning will happen when they encounter more rare words in Tiers 2 and 3.

Tier 2 includes more complex words that are synonyms for words or ideas that children already know. For example, instead of happy, children learn excited, thrilled, and overjoyed. Instead of cold, they learn freezing, frigid, icy, frostbitten. These are book-words, words that tend to be used in books, across content areas (science, history, geography, etc.). As a result, hearing these words in meaningful contexts is directly preparing your child to read literary texts and content area texts down the road. As a result, these words are sometimes called "academic vocabulary" because they help children read and write in school contexts.

At the same time, these words may or may not come up in your ordinary conversations, even if you are talking to your child a lot and have a large vocabulary. Even very smart, highly educated adults tend to use the same words over and over again in our speech, as indicated in this study, which found that children's books include more complex and rare vocabulary than conversations between adults. Reading books to your children, therefore, pushes you to use more Tier 2 words than you would naturally.

Tier 3 words are content-specific words. We could think of these words as science or history vocabulary; words like planet, mammal, canal, or pharaoh. These words are also important for success in school, but they are important because of the concepts they represent; when children learn these words they are acquiring new knowledge as well as vocabulary. Background knowledge is critical for reading comprehension, so building this vocabulary and knowledge also supports long-term reading success. These words also rarely come up in everyday conversation, but often come up in great children's books, especially works of nonfiction. My Tier 3 vocabulary has greatly expanded since having a toddler, to include words like: excavator, backhoe loader, motor grader, feller buncher, and much more!

So vocabulary is a big reason you are reading to your kids every day, even when the going gets tough. However, the books themselves also provide an important learning tool. As children watch you read and handle books, they develop concepts of print, including knowledge about how to hold a book, how words the words in the book tell the story, how text moves across the page, how to turn pages, and that letters make up words. All of these mechanisms are opaque to children at first! For a while, Will would want me to read to him in the car, even if it was dark, because he didn't understand that I needed to see the words to read them! Now he is showing much more interest in identifying letters and words on the pages, in addition to enjoying the story. Two strategies can help kids develop these kinds of knowledge about print:

- talking about the print in books as you read (called print referencing; Justice & Ezell, 2000)

- giving kids lots of opportunities to handle books on their own

Finally, reading aloud to children builds their motivation to learn to read. They get to experience the wonders of reading before they have to do the work of reading: engaging characters, exciting plots, beautiful language, and worlds of new facts. Unlike vocabulary flash cards, or alphabet tracing or copying, or phonics games or worksheets, reading aloud with your child helps build literacy skills during in an authentic way. The purpose of reading is reading, and reading aloud to children helps them connect reading with your love and attention and develop positive associations that can last a lifetime.

So keep up the good work!

Thanks Laura! I'll definitely be doing more work to draw attention to the print on the page. :)

ReplyDelete